If you walk west along rue de Rivoli from Hotel de Ville toward the Louvre, you will pass a tall stone tower that looks like it should be attached to something, but is standing alone in the middle of a tiny park. It is decorated with Gothic ornaments and topped with gargoyles, just like Notre Dame or any other Gothic ediface, but…where’s the church?

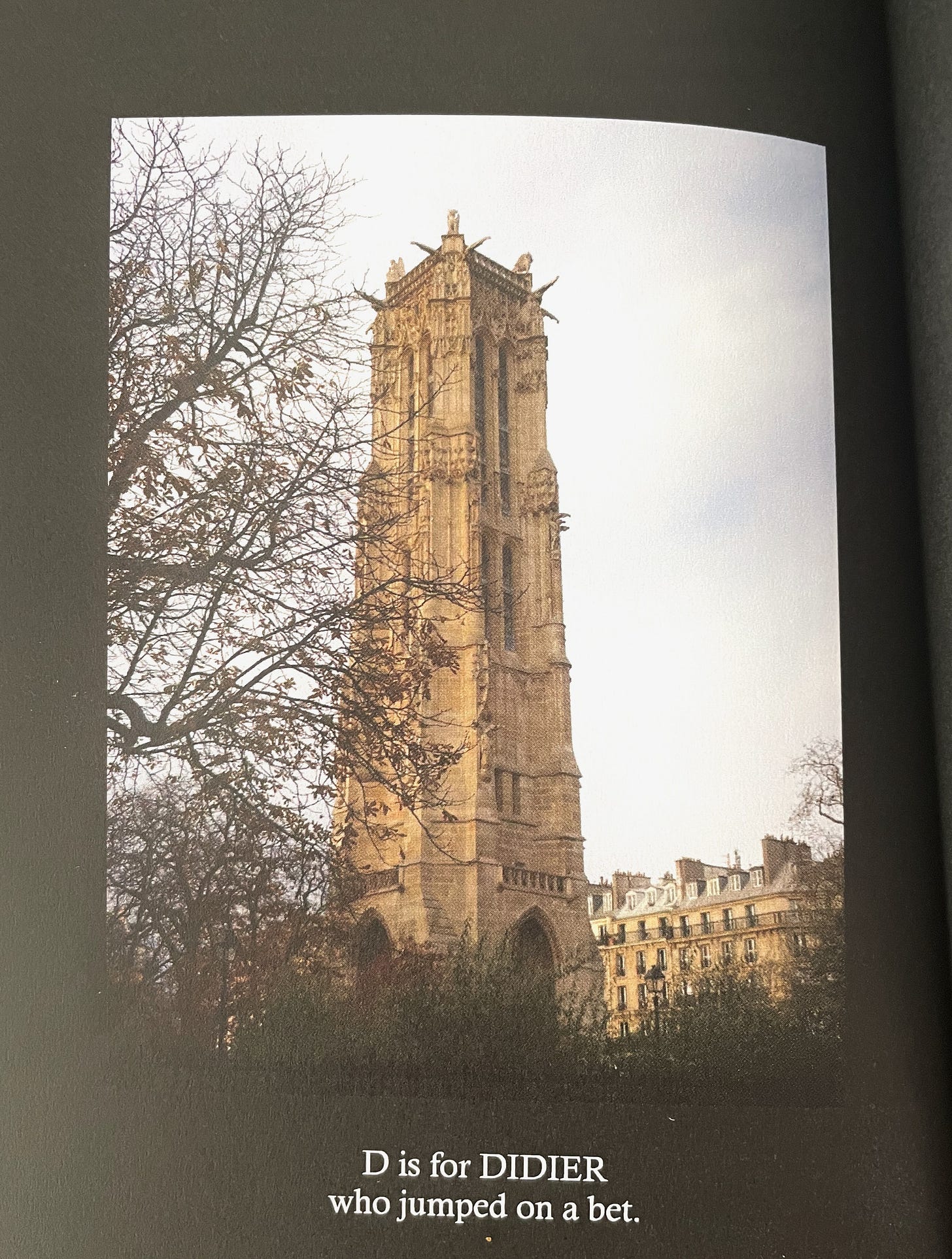

I have long been fascinated by the Tour Saint-Jacques. I even used it as the letter “D” in my Alphabet of Paris Zombies.

While planning my next young adult book, set in Paris in the late 19th century, I chose the Tower as headquarters and lair for a young inventor and thief. It’s the tallest thing around, I figured. And from the top, it must provide an unparalleled strategic view of the city. When I found it had been used as a shot tower (molten lead was dropped from the top of the tower through a sieve, droplets cooled as they fell and landed far below in a trough of cold water having solidified into rifle shot…tiny bullets) I knew I had chosen the right place.

Soon after I moved back to France in 2005, the tower was closed for renovations, and remained that way for years. Ever since, it’s been sitting there, pretty and clean and stabilized, but still closed off. Or so I thought. I recently discovered that it is open to visitors by guided tour 6 months a year on weekends. So last Sunday Tallie, Tibor and I took an hour-long visit, which included climbing the tower’s 291 steps to the top.

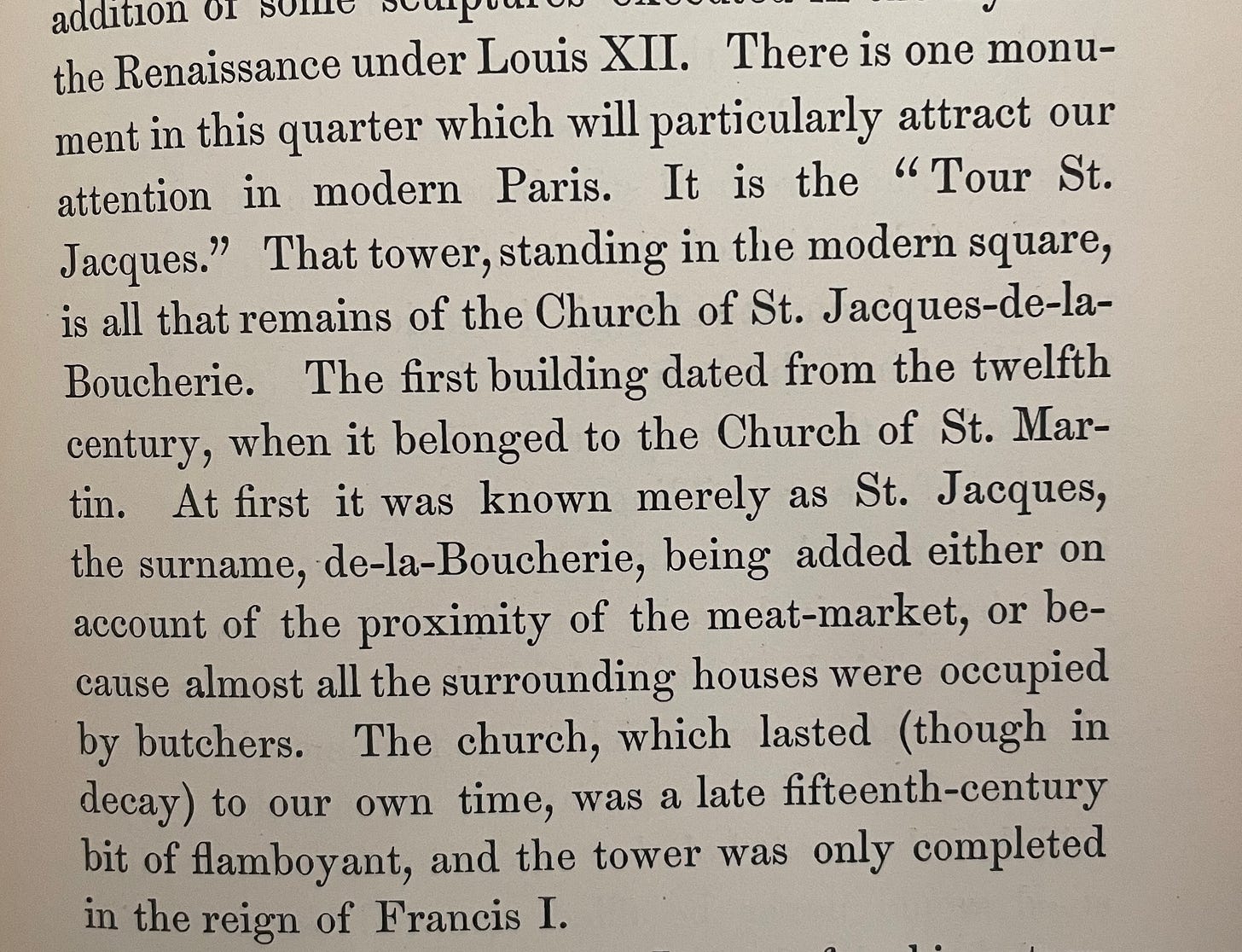

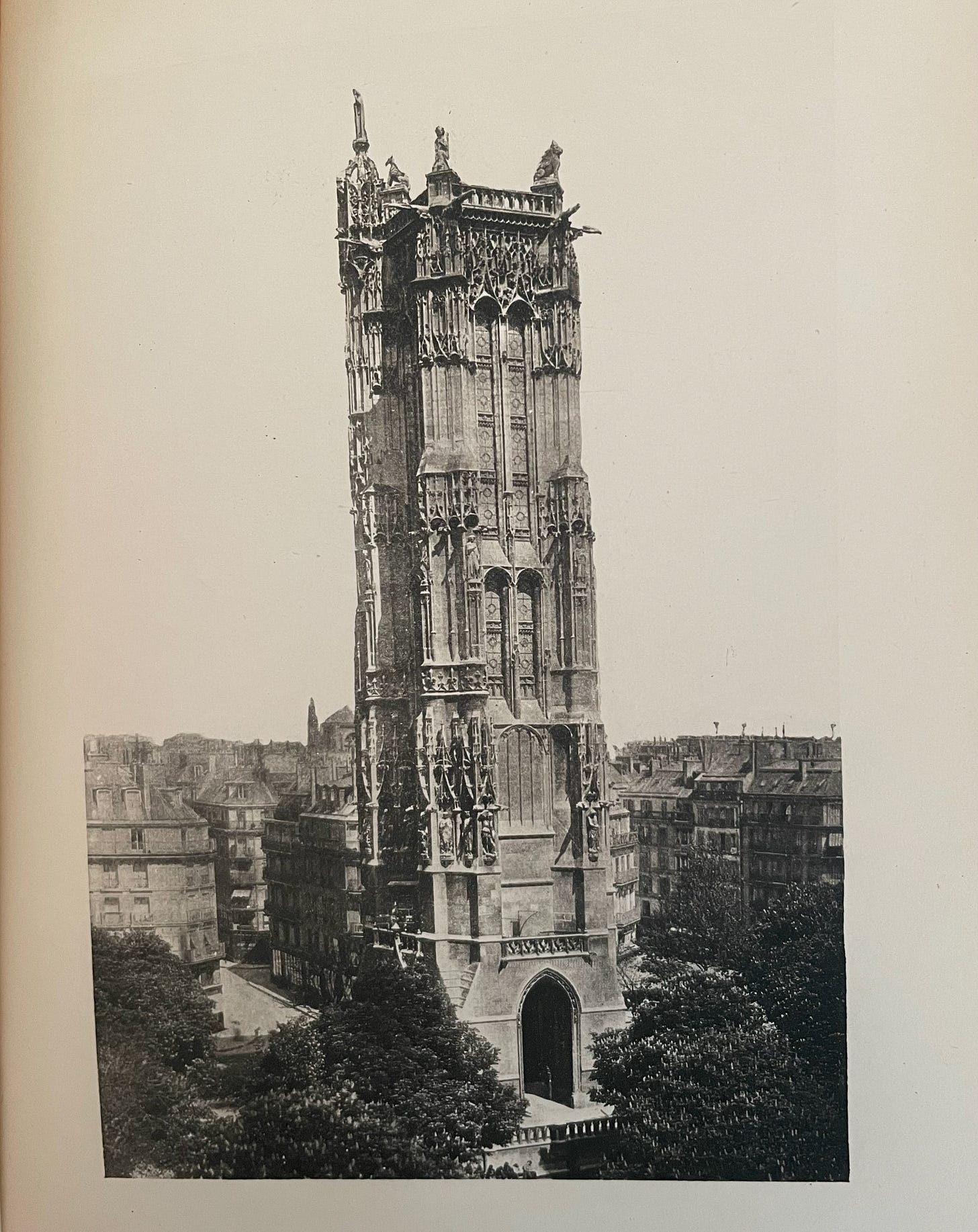

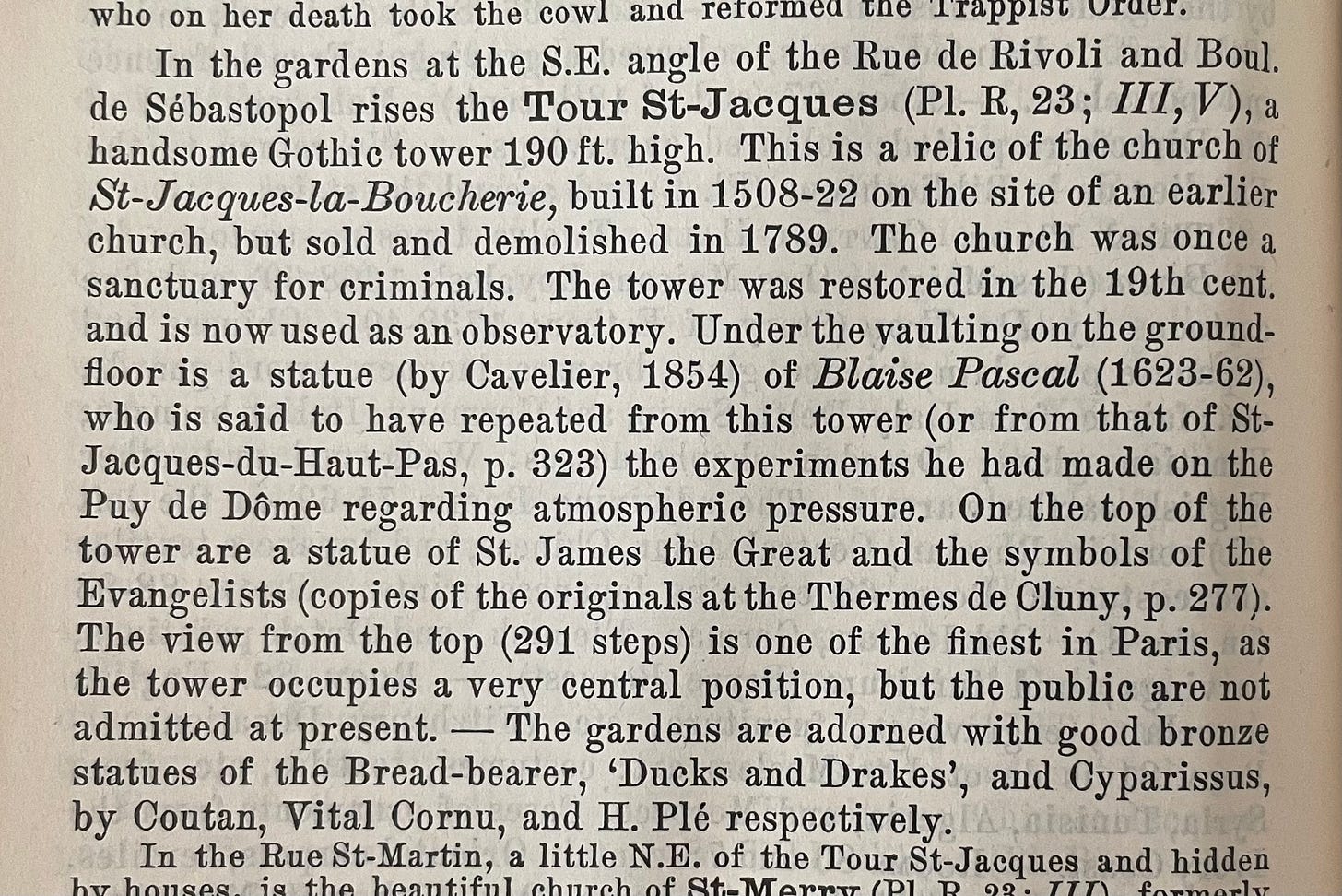

But first, to look into the history of this enigmatic solitary tower, I’ll start with the oldest source in my incredibly geeky home library: my 1899 edition of “Paris: Its Sites, Monuments and History.”

then a little later:

My 1924 edition of Baedeker’s holds a few more details. (But gets the dates a bit wrong.)

In a much more recent (and more whimsical) recounting, the French author Régine Deforges, wrote in her 2011 “Le Paris de mes Amours” (my own translation):

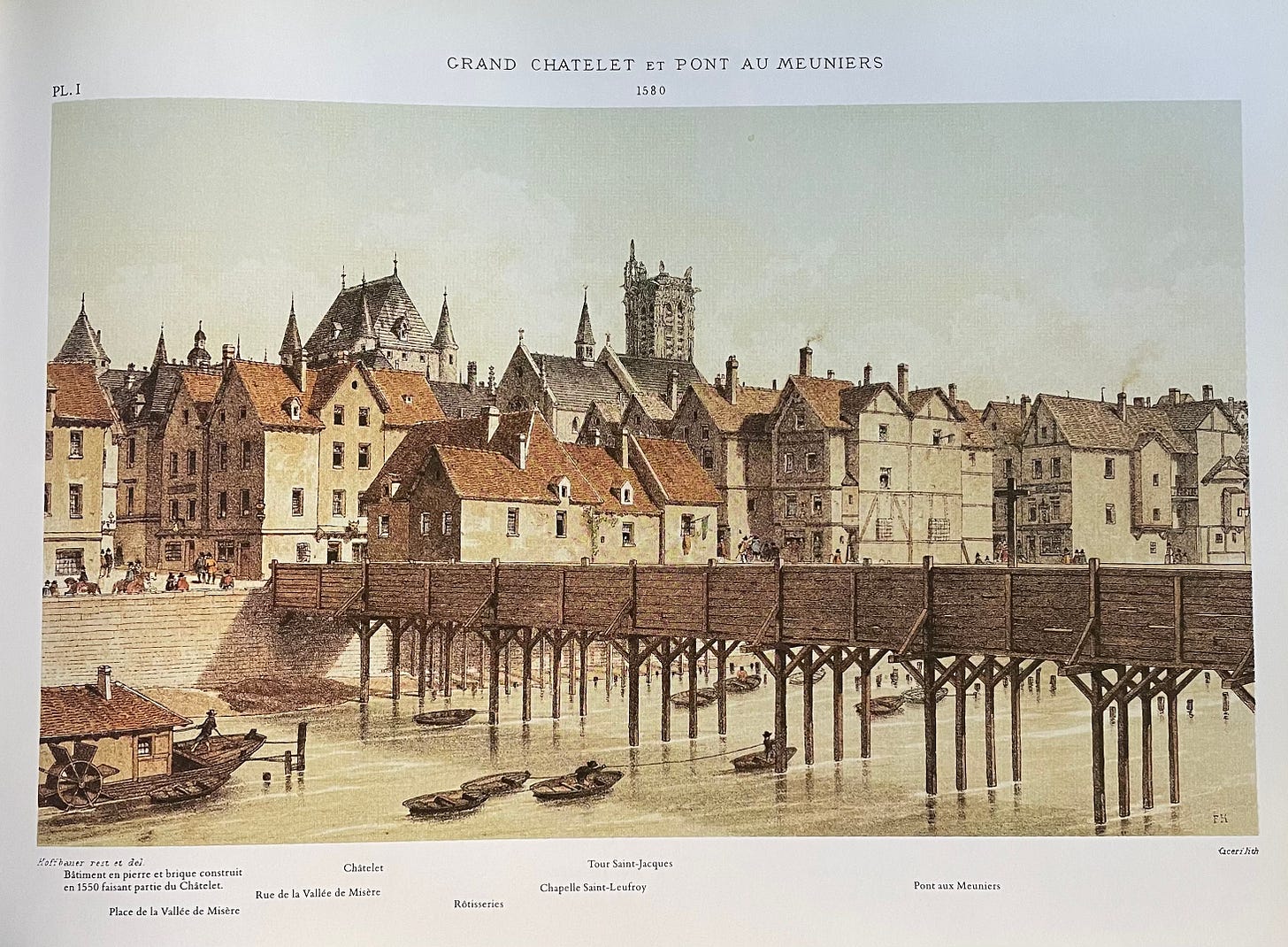

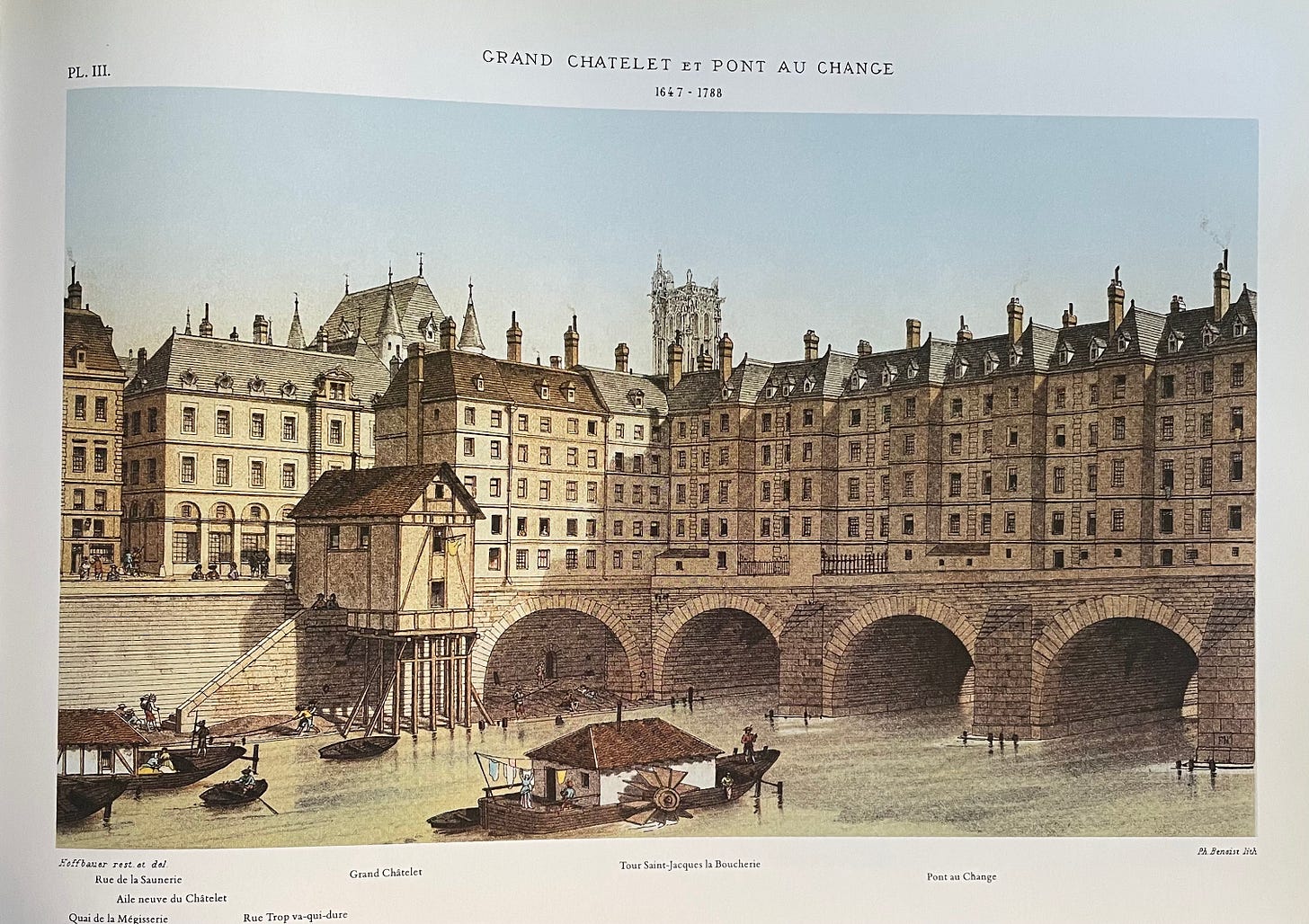

“In bad weather, certain evenings, the Tour Saint-Jacques looks like a Victor Hugo drawing. I’m never too reassured when I cross the little square that surrounds it. I look up to make sure no gargoyles will fall on my head, despite the renovation work undertaken. The Tour Saint-Jacques flanked the portal of a church that goes back to Carolingian times and was rebuilt in the 11th and 14th centuries. Public writers did business in the stands leaning against the north side of the church. The most famous of these scribes was Nicolas Flamel who lived on rue des Ecrivains. Nicolas Flamel, who was wealthy, gifted the church with an ornate lateral portal, on its tympanum a bas-relief showing him wearing the garb of a sworn writer, accompanied by his wife Pernelle, both kneeling at the feet of the Virgin Mary. The Church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie was sold in 1797, then demolished. Only the tower, which served as the church’s bell tower, was spared from destruction. It was the Parisian starting point for the pilgrimage to Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle. At its summit, a huge statue of the saint indicated the direction of the path to the pilgrims.

The church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie had the right of asylum. In 1405 a room was installed in the the sanctuary’s vault for those who wished to take refuge there. Where do the assassins and thieves go now, after finding shelter for centuries in the church? Are the street people stretched out on the square’s benches their descendants? Does the phantom of Nicolas Flamel, buried in the church, keep them company? Could it have been in memory to Blaise Pascal and his barometric experiments made at the top of the tower that it was spared at the moment of the Revolution?”

(Apparently Mme Deforges doesn’t have a high esteem of street people. But, then again, who has ever accused the French of being politically correct?)

Almost every source I saw mentioned that this church offered the right of asylum, or as Baedeker put it, “was once a sanctuary for criminals.” We’ve all read books or seen films where the hero is struggling to make it to a church to find safety from the law. But this was a real thing, and this church was famous enough for it to provide a room for those escaping the law. Just imagine what kind of people were turning up!

I find this absolutely fascinating. So did king François I, however, and he decided he didn’t like the fact that this effectively put the church above the government. He abolished the right to asylum in 1539.

Armed with all of this juicy historical information, I booked tickets and dragged my not-terribly-enthusiastic kids (“291 steps!?”) along to the tower tour. We were greeted by a guide who informed us we were one of only 17 people allowed to go up the tower at a time. She explained that the reason it was closed in winter was because of the high winds and bad weather at the top. At which point I had to resort to bribery to convince Tibor to continue with the ascent.

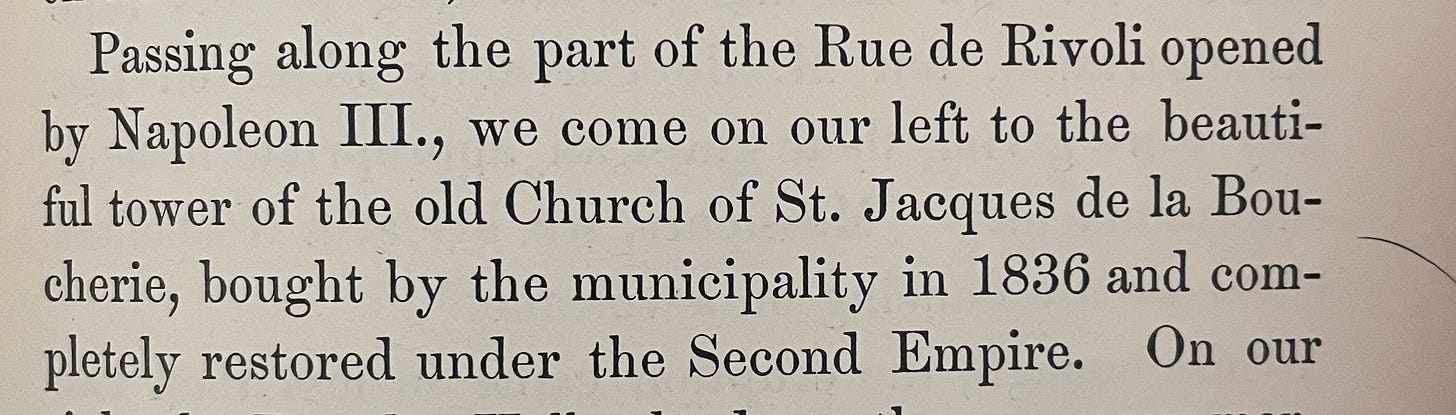

We started in the park, which would have been below-ground before Haussmann (under Napoleon III) dug up the whole neighborhood to make a straight path for rue de Rivoli. The workers dug so low that it exposed the foundations of the tower. So a huge, ornate pedestal was commissioned to surround and protect the base.

The guide unlocked the gate and we climbed the stairs to stand under the vault in front of a larger-than-life statue of Blaise Pascal.

The guide told us that the 12th century church had, indeed, been enlarged and paid for in the 14th and 16th centuries by Paris’s wealthy butchers, who lived nearby. “Dirty businesses” (like slaughtering animals) had been pushed off of the Ile de la Cité and out of the “center” of town, and the butchers had taken up residence near the market area that became Les Halles.

The church had other wealthy patrons, including Nicolas Flamel, who made his riches from real estate, not from his experiments with alchemy. (As was reported in that historically reliable treatise, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.) Flamel married an even wealthier woman and they helped pay for part of the church. They were buried beneath its nave in 1418 and their bones later transferred to the catacombs.*

The bell tower was built from 1509-1523 in flamboyant style. (Look at the architectural embellishments and think “flames” — you’ll see where the style got its name.)

Then from 1647-1648 Blaise Pascal did his experiments on the weight of air in this tower (or in the tower of another church named almost the same thing, thus confusing historians everywhere) resulting in his discovery of atmospheric pressure.

There was damage to the church and bell tower during the Revolution. The previous tower roof sculptures of 3 evangelists and St. Jacques were destroyed. Our guide told us that the revolutionaries hacked through ropes, causing the bells to crash to the ground, inflicting destruction on the tower’s base.

In 1797 the Revolutionary government sold the church for scrap. It became a “stone quarry” feeding the city’s building works. But the sales contract specified that the tower was to be saved. Why? Mme Deforge guessed it was out of respect for Pascal’s experiments. I surmised it might have been haunted by Nicolas Flamel’s ghost. (A much more exciting explanation.) But the alchemist-slash-real-estate-baron was long gone by the time the bell tower was erected. So there goes that theory.

It was bought by an entrepreneur named Dubois, who is the one who transformed it into a shot tower, transforming molten lead into rifle shot. Our guide told us that following several fires (imagine that!) the city bought the tower back in 1836 and integrated it into Haussmann’s plans with architect Théodore Ballu in charge of renovations. It was declared a national monument in 1862.

In 1891 it began being used as a meteorological station, and continued in this capacity for half of the 20th century. In the early 21st century it was discovered that the renovations had weakened the tower. So in 2006 a new renovation was undertaken, this time sourcing limestone from the same quarry in the Oise where the original stones were sourced, thus stabilizing the cracking tower.

Now it acts as the starting point for the pilgrimage road to Compostelle and, as such, is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The tower’s history explained, we began the climb. There is only one way up and down the tower, and this is it:

I was prepared to hike all the way to the top, but before long, the guide went through a side door and led us into this room:

which held decorative chunks of the original building that had either broken off or were replaced.

I took about a million photos of this guy:

because in my story this is what happens:

No thief had a better view in all of Paris. Martin could spy, unperceived, on everyone for blocks around. And now, what he spied was a figure in a blue smock over white pants flitting like a moth from shadow to shadow, avoiding the dim pools of light cast by the streetlamps.

He grabbed his spyglass from where it hung around the gargoyle’s neck. “Thanks, Victor,” he murmured to the statue, and focused his lens on the figure below.

Please tell me this is not a Victor…

…with his dashing mustache and goatee, pointy ears, and one remaining horn!

So I embarrassed my kids by doing a whole photo shoot of Victor and this guy…

who, unlike Victor, does not have a funnel and a spout and is thus a mere chimera…decoration only, no utility. So pff…he might not even get a name.

We then proceeded up the next set of stairs to this room:

which was where the meteorological experiments took place until around 1950.

The paint is wonderfully crumbled.

When you look up, you see all the way to the top. And the stained glass windows, which were installed during Ballu’s renovation, bear the initials NF for Nicolas Flamel and TB, for (surprise, surprise) Théodore Ballu.

When I saw this room, my heart gave a little leap. I love it when reality fits perfectly inside my fiction. (It happens more often then you think. Which is one way I know I’m on the right track.)

This is my description of Martin’s hideout:

The thief sat on a golden throne in his sumptuous lair, scheming his next heist. The room was lined with diamonds and gold with mountains of money stacked here and there. At least, that’s how it appeared in his mind. In reality, it was a drafty room furnished with a straw-stuffed pallet for sleeping, a box for his clothes and belongings, a stack of books that he used to teach himself to read, and a rickety chair, on which he balanced, leaning back on its hind legs. That, and a table holding a million parts and pieces and several half-made and barely made inventions. He called it his lab. He was not in the room, however. He was in his thinking place, outside on the balcony.

Perfect, right?

So, on to the next set of stairs. Finally we found ourselves on the roof of the tower, with a panoramic view of Paris, surrounded by giant statues representing the 4 evangelists.

Over the years and through many museums, I’ve taught my kids the symbols that are the key to reading European art. (My M.A. was in medieval painting.) So when I asked who the statues represented, they knew the answers: Matthew - angel (it’s supposed to be a “man” but it’s always a man with wings, so let’s just say angel). Mark - lion. Luke - ox. And John - eagle.

These are replacement sculptures for the originals, destroyed in the Revolution. (There were originally 3 + St. Jacques.) These four are apparently copies of others that are at the Cluny Museum.

Then, of course, there’s the massive St. Jacques pointing the way to Tours, which is the next step on pilgrims’ long walk to Compostelle, Spain.

Ooh - and look…a trap door. I’m DEFINITELY using that in my story. (Tibor freaked out when I tried to nudge it open, so I’ll save further research for another time when he’s not with me.)

So here’s the view…

And here’s a shot of me in my element. (History, art, architecture, urban exploring, and storytelling…all in one. Couldn’t get better.)

The 291 steps down were a cinch. And once at the bottom, I couldn’t help but look up. How majestic is that?

The whole family gave the visit a thumbs-up, with Tibor saying his favorite thing was the view from above on the Pompidou Center and Tallie choosing sitting at the top and looking out over the city. As for me, I’ll take the whole thing, every inch of it, and make it mine.

Tickets are 12 euros for adult/10 for students. Reserve here.

*Fun fact…Nicolas Flamel’s funerary stone was set high up in a column in the church, above an image of the Virgin. When the church was demolished, a fruit and vegetable merchant bought the engraved slab of stone and used it to hold his spinach. The city of Paris convinced him to sell them the stone, and it is now in the Cluny Museum.